R-TF-028-001 AI Description

Table of contents

- Purpose

- Scope

- Algorithm summary

- Algorithm Classification

- Statistical Acceptance Framework

- Description and Specifications

- ICD Category Distribution and Binary Indicators

- Erythema Intensity Quantification

- Desquamation Intensity Quantification

- Induration Intensity Quantification

- Pustule Intensity Quantification

- Crusting Intensity Quantification

- Xerosis Intensity Quantification

- Swelling Intensity Quantification

- Oozing Intensity Quantification

- Excoriation Intensity Quantification

- Lichenification Intensity Quantification

- Wound Characteristic Assessment

- Erythema Surface Quantification

- Wound Surface Quantification

- Body Surface Segmentation

- Hair Loss Surface Quantification

- Inflammatory Nodular Lesion Quantification

- Acneiform Lesion Type Quantification

- Acneiform Inflammatory Lesion Quantification

- Hive Lesion Quantification

- Nail Lesion Surface Quantification

- Hypopigmentation or Depigmentation Surface Quantification

- Hyperpigmentation Surface Quantification

- Follicular and Inflammatory Pattern Identification

- Hair Follicle Quantification

- Inflammatory Nodular Lesion Pattern Identification

- Dermatology Image Quality Assessment (DIQA)

- Domain Validation

- Skin Surface Segmentation

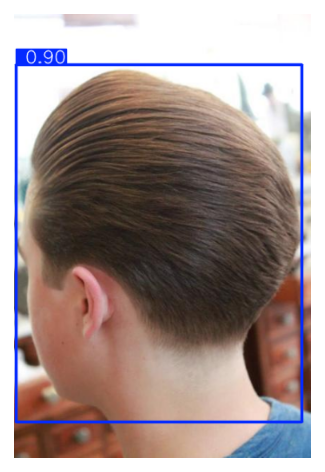

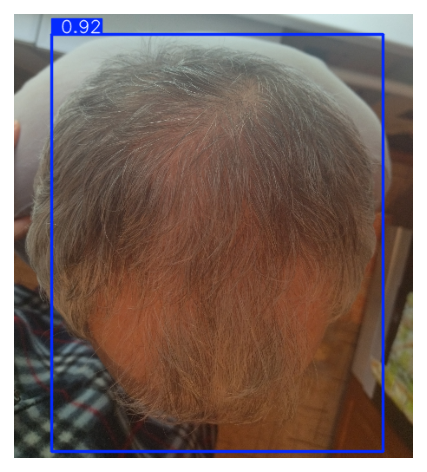

- Head Detection

- Data Specifications

- Other Specifications

- Cybersecurity and Transparency

- Specifications and Risks

- Integration and Environment

- References

- Traceability to QMS Records

Purpose

This document defines the specifications, performance requirements, and data needs for the Artificial Intelligence (AI) models used in the Legit.Health Plus device.

Scope

This document details the design and performance specifications for all AI algorithms integrated into the Legit.Health Plus device. It establishes the foundation for the development, validation, and risk management of these models.

This description covers the following key areas for each algorithm:

- Algorithm description, clinical objectives, and justification.

- Performance endpoints and acceptance criteria.

- Specifications for the data required for development and evaluation.

- Requirements related to cybersecurity, transparency, and integration.

- Links between the AI specifications and the overall risk management process.

Algorithm summary

| ID | Model Name | Type | Task Type | Visible Signs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ICD Category Distribution and Binary Indicators | 🔬 Clinical | Classification | All Dermatological Conditions |

| 2 | Erythema Intensity Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Ordinal Classification | Erythema |

| 3 | Desquamation Intensity Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Ordinal Classification | Desquamation |

| 4 | Induration Intensity Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Ordinal Classification | Induration |

| 5 | Pustule Intensity Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Ordinal Classification | Pustule |

| 6 | Crusting Intensity Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Ordinal Classification | Crusting |

| 7 | Xerosis Intensity Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Ordinal Classification | Xerosis |

| 8 | Swelling Intensity Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Ordinal Classification | Swelling |

| 9 | Oozing Intensity Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Ordinal Classification | Oozing |

| 10 | Excoriation Intensity Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Ordinal Classification | Excoriation |

| 11 | Lichenification Intensity Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Ordinal Classification | Lichenification |

| 12 | Wound Perilesional Erythema Assessment | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Perilesional Erythema |

| 13 | Damaged Wound Edges Assessment | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Damaged Edges |

| 14 | Delimited Wound Edges Assessment | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Delimited Edges |

| 15 | Diffuse Wound Edges Assessment | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Diffuse Edges |

| 16 | Thickened Wound Edges Assessment | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Thickened Edges |

| 17 | Indistinguishable Wound Edges Assessment | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Indistinguishable Edges |

| 18 | Perilesional Maceration Assessment | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Perilesional Maceration |

| 19 | Fibrinous Exudate Assessment | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Fibrinous Exudate |

| 20 | Purulent Exudate Assessment | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Purulent Exudate |

| 21 | Bloody Exudate Assessment | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Bloody Exudate |

| 22 | Serous Exudate Assessment | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Serous Exudate |

| 23 | Biofilm-Compatible Tissue Assessment | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Biofilm-Compatible Tissue |

| 24 | Wound Affected Tissue: Bone | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Bone Tissue |

| 25 | Wound Affected Tissue: Subcutaneous | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Subcutaneous Tissue |

| 26 | Wound Affected Tissue: Muscle | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Muscle Tissue |

| 27 | Wound Affected Tissue: Intact Skin | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Intact Skin |

| 28 | Wound Affected Tissue: Dermis-Epidermis | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Dermis-Epidermis Tissue |

| 29 | Wound Bed Tissue: Necrotic | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Necrotic Tissue |

| 30 | Wound Bed Tissue: Closed | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Closed Wound |

| 31 | Wound Bed Tissue: Granulation | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Granulation Tissue |

| 32 | Wound Bed Tissue: Epithelial | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Epithelial Tissue |

| 33 | Wound Bed Tissue: Slough | 🔬 Clinical | Binary Classification | Slough Tissue |

| 34 | Wound Stage Classification | 🔬 Clinical | Multi Class Classification | Wound Stage |

| 35 | Wound AWOSI Score Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Ordinal Classification | Wound AWOSI Score |

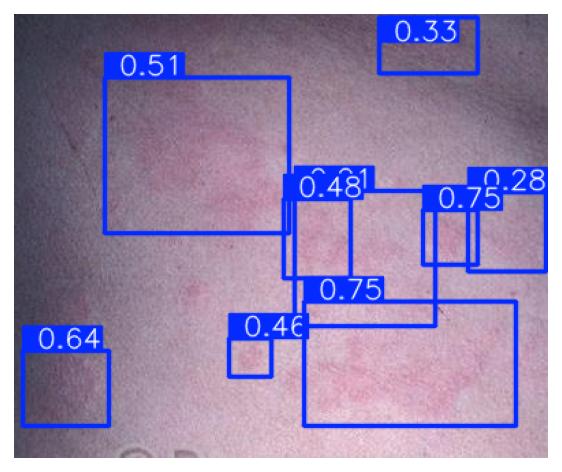

| 36 | Erythema Surface Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Segmentation | Erythema |

| 37 | Wound Bed Surface Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Segmentation | Wound Bed |

| 38 | Angiogenesis and Granulation Tissue Surface Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Segmentation | Angiogenesis and Granulation Tissue |

| 39 | Biofilm and Slough Surface Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Segmentation | Biofilm and Slough |

| 40 | Necrosis Surface Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Segmentation | Necrosis |

| 41 | Maceration Surface Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Segmentation | Maceration |

| 42 | Orthopedic Material Surface Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Segmentation | Orthopedic Material |

| 43 | Bone, Cartilage, or Tendon Surface Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Segmentation | Bone, Cartilage, or Tendon |

| 44 | Hair Loss Surface Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Segmentation | Alopecia |

| 45 | Hair Follicle Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Object Detection | Hair Follicles |

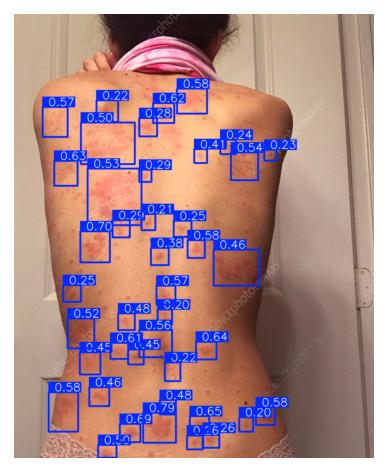

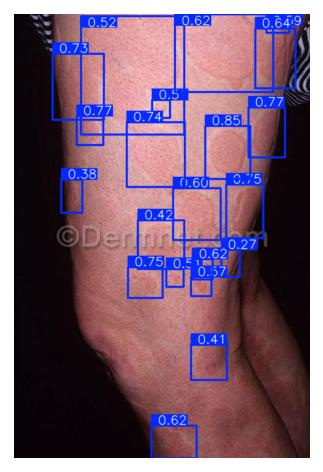

| 46 | Inflammatory Nodular Lesion Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Multi Class Object Detection | Nodule, Abscess, Non-draining Tunnel, Draining Tunnel |

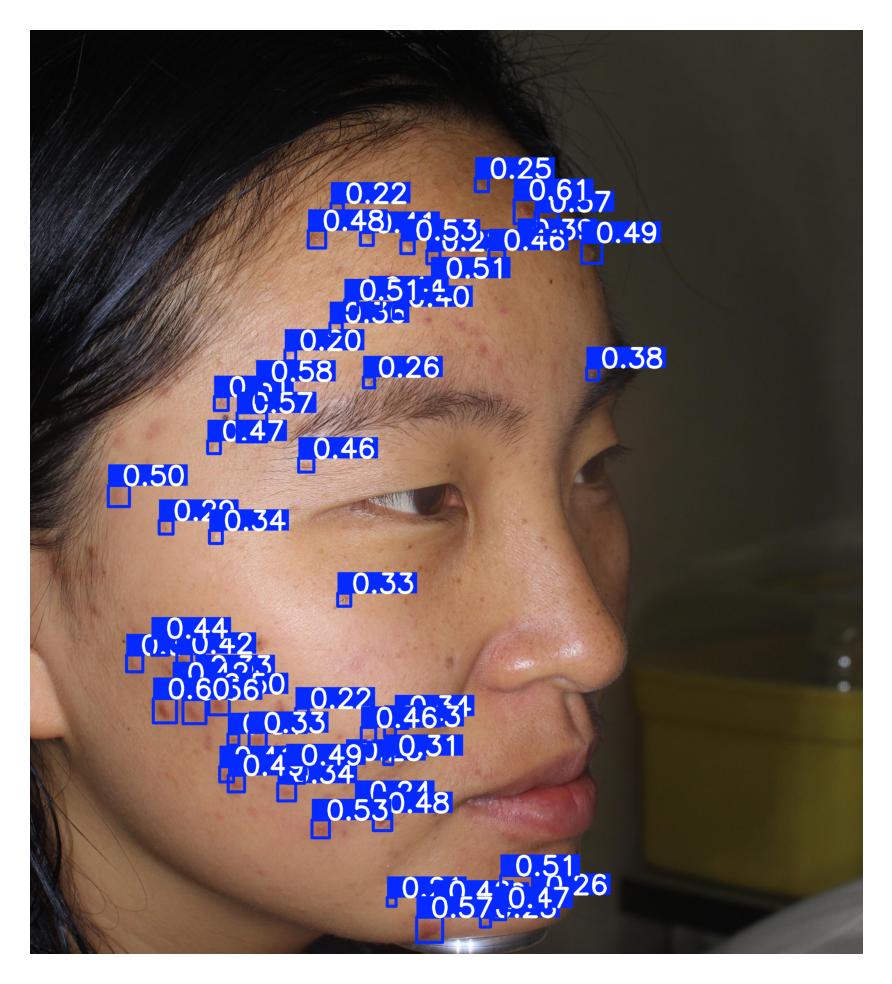

| 47 | Acneiform Lesion Type Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Multi Class Object Detection | Papule, Pustule, Cyst, Comedone, Nodule |

| 48 | Acneiform Inflammatory Lesion Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Object Detection | Inflammatory Lesion |

| 49 | Hive Lesion Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Object Detection | Hive |

| 50 | Nail Lesion Surface Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Segmentation | Nail Lesion |

| 51 | Hypopigmentation or Depigmentation Surface Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Segmentation | Hypopigmentation or Depigmentation |

| 52 | Hyperpigmentation Surface Quantification | 🔬 Clinical | Segmentation | Hyperpigmentation |

| 53 | Follicular and Inflammatory Pattern Identification | 🔬 Clinical | Classification | — |

| 54 | Inflammatory Pattern Identification | 🔬 Clinical | Multi Task Classification | Hurley Stage, Inflammatory Activity |

| 55 | Body Surface Segmentation | 🛠️ Non-Clinical | Multi Class Segmentation | — |

| 56 | Dermatology Image Quality Assessment (DIQA) | 🛠️ Non-Clinical | Regression | — |

| 57 | Domain Validation | 🛠️ Non-Clinical | Classification | — |

| 58 | Skin Surface Segmentation | 🛠️ Non-Clinical | Segmentation | — |

| 59 | Head Detection | 🛠️ Non-Clinical | Object Detection | — |

Algorithm Classification

The AI algorithms in the Legit.Health Plus device are classified into two categories based on their relationship to the device's intended purpose as defined in the Technical Documentation.

Clinical Models

Clinical models are AI algorithms that directly fulfill the device's intended purpose by providing one or more of the following outputs to healthcare professionals:

- Quantitative data on clinical signs (severity measurement of dermatological features)

- Interpretative distribution of ICD categories (diagnostic support for skin conditions)

These models:

- Directly contribute to the device's medical purpose of supporting healthcare providers in assessing skin structures

- Provide outputs that healthcare professionals use for assessment, monitoring, or treatment decisions

- Generate quantitative measurements or probability distributions that constitute medical information

- Are integral to the clinical claims and intended use of the device

- Are subject to full clinical validation and regulatory requirements under MDR 2017/745 and RDC 751/2022

Non-Clinical Models

Non-clinical models are AI algorithms that enable the proper functioning of the device but do not themselves provide the outputs defined in the intended purpose. These models:

- Perform quality assurance, preprocessing, or technical validation functions

- Ensure that clinical models receive appropriate inputs and operate within their validated domains

- Support equity, bias mitigation, and performance monitoring across diverse populations

- Do not generate quantitative data on clinical signs or interpretative distributions of ICD categories

- Do not independently provide medical information used for diagnosis, monitoring, or treatment decisions

- Serve as auxiliary technical infrastructure supporting clinical model performance and patient safety

Important Distinctions:

- Clinical models directly fulfill the intended purpose: "to provide quantitative data on clinical signs and an interpretative distribution of ICD categories to healthcare professionals for assessing skin structures."

- Non-clinical models enable clinical models to function properly but do not themselves provide the quantitative or interpretative outputs defined in the intended purpose.

Statistical Acceptance Framework

Throughout this document, each model's Endpoints and Requirements section states that performance thresholds "must be achieved with 95% confidence intervals." This section provides the formal, unambiguous definition of that acceptance rule, which is applied consistently across all models in the corresponding validation results reported in R-TF-028-005 Development Report.

Definition of PASS

A metric achieves its threshold with 95% confidence intervals when the lower bound of the bootstrap 95% confidence interval satisfies the stated threshold inequality:

| Threshold direction | Example | PASS condition |

|---|---|---|

| Upper-bounded (≤) | RMAE ≤ 20% | 95% CI lower bound ≤ threshold |

| Lower-bounded (≥) | IoU ≥ 0.85, Accuracy ≥ 50% | 95% CI lower bound ≥ threshold |

This rule applies identically to overall performance evaluation and to every subgroup in bias analysis (e.g., per-Fitzpatrick-type, per-severity stratum).

Rationale

- For lower-bounded metrics (higher is better, e.g., IoU, Accuracy, AUC), requiring the CI lower bound to meet the threshold ensures — with 95% confidence — that the model's true performance exceeds the acceptance criterion.

- For upper-bounded metrics (lower is better, e.g., RMAE), requiring the CI lower bound to meet the threshold verifies that the model's best-case plausible error is within the acceptable range. When sample sizes are small, the CI may be wide; in such cases, subgroups where the point estimate (mean) exceeds the threshold but the CI lower bound remains below it are flagged as PASS with the understanding that additional data collection is recommended to narrow the confidence interval and strengthen the evidence.

Reporting convention

All validation results in R-TF-028-005 report three values for each metric and subgroup:

- Point estimate (mean)

- 95% bootstrap confidence interval (lower bound, upper bound)

- Outcome — PASS or NO PASS, determined solely by the rule above

Description and Specifications

ICD Category Distribution and Binary Indicators

Model Classification: 🔬 Clinical Model

Description

ICD Category Distribution

We employ a deep learning model to analyze clinical or dermoscopic lesion images and output a probability distribution across ICD-11 categories. Deep learning-based image classifiers can be designed to recognize fine-grained disease categories with high variability, leveraging mechanisms to capture both local and global image features [1,2,9].

Given an RGB image, this model outputs a normalized probability vector:

where each corresponds to the probability that the lesion belongs to the -th ICD-11 category, and .

The system highlights the top five ICD-11 disease categories, each accompanied by its corresponding code and confidence score, thereby supporting clinicians with both ranking and probability information—a strategy shown to enhance diagnostic confidence and interpretability in multi-class dermatological AI systems [2,3].

Binary Indicators

Binary indicators are derived from the ICD-11 probability distribution as a post-processing step using a dermatologist-defined mapping matrix. The protocol for creating, validating, and maintaining this matrix is defined in R-TF-028-004 Data Annotation Instructions - Binary Indicator Mapping. Each indicator reflects the aggregated probability that a case belongs to clinically meaningful categories requiring differential triage or diagnostic attention.

The six binary indicators are:

- Malignant: probability that the lesion is classified as a confirmed malignancy (e.g., melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma).

- Pre-malignant: probability of conditions with malignant potential (e.g., actinic keratosis, Bowen's disease).

- Associated with malignancy: benign or inflammatory conditions with frequent overlap or mimicry of malignant presentations (e.g., atypical nevi, pigmented seborrheic keratoses).

- Pigmented lesion: probability that the lesion belongs to the pigmented subgroup, important for melanoma probability assessment.

- Urgent referral: lesions associated with conditions typically requiring dermatological evaluation within 48 hours (e.g., suspected melanoma, rapidly growing nodular lesions, bleeding or ulcerated malignancies).

- High-priority referral: lesions that should be seen within 2 weeks according to dermatology referral guidelines (e.g., suspected non-melanoma skin cancer, premalignant lesions with malignant potential).

For categories and 6 indicators, the mapping matrix has a size of . Thus, the computation of each indicator is defined as:

where is the probability for the -th ICD-11 category, and is the binary weight coefficient () that indicates whether category contributes to indicator .

Objectives

ICD Category Distribution Objectives

- Improve diagnostic accuracy, aiming for an uplift of approximately 10–15% in top-1 and top-5 prediction metrics compared to baseline approaches [4,5,6].

- Assist clinicians in differential diagnosis, especially in ambiguous or rare cases, by presenting a ranked shortlist that enables efficient decision-making.

- Enhance trust and interpretability—leveraging attention maps to offer transparent reasoning and evidence for suggested categories [7].

Justification: Presenting a ranked list of likely conditions (e.g., top-5) is evidence-based.

- In reader studies, AI-based multiclass probabilities improved clinician accuracy beyond AI or physicians alone, with the largest benefit for less experienced clinicians [8,9].

- Han et al. reported sensitivity +12.1%, specificity +1.1%, and top-1 accuracy +7.0% improvements when physicians were supported with AI outputs including top-k predictions [9].

- Clinical decision support tools providing ranked differentials improved diagnostic accuracy by up to 34% without prolonging consultations [10].

- Systematic reviews confirm that AI assistance consistently improves clinician accuracy, especially for non-specialists [11,12].

Binary Indicator Objectives

- Clinical triage support: Provide clinicians with clear case-prioritization signals, improving patient flow and resource allocation [13, 14].

- Malignancy risk quantification: Objectively assess malignancy and premalignancy likelihood to reduce missed diagnoses [15].

- Referral urgency standardization: Align algorithm outputs with international clinical guidelines for dermatology referrals, e.g., NICE and EADV recommendations: urgent (≤48h), high-priority (≤2 weeks) [16, 17].

- Improve patient safety: Flag high-risk pigmented lesions for expedited evaluation, ensuring melanoma is not delayed in triage [18, 19].

- Reduce variability: Decrease inter-observer variation in urgency assignment by providing consistent, evidence-based binary outputs [20].

Justification:

- Binary classification systems for malignancy probability have demonstrated clinical utility in improving referral appropriateness and reducing delays [13, 15].

- Standardized triage tools based on objective criteria show reduced inter-observer variability (κ improvement from 0.45 to 0.82) compared to subjective clinical judgment alone [20].

- Integration of urgency indicators into clinical workflows has been associated with improved melanoma detection rates and reduced time to specialist evaluation [18, 19].

Endpoints and Requirements

ICD Category Distribution Endpoints and Requirements

Performance is evaluated using Top-k Accuracy compared to expert-labeled reference standard. In large-scale "long-tail" dermatology (where many diseases are rare), Top-1 accuracy naturally drops, while Top-3 and Top-5 become the primary indicators of clinical utility.

| Metric | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Top-1 Accuracy | ≥ 50% | Meets minimum utility |

| Top-3 Accuracy | ≥ 60% | Reliable differential assessment |

| Top-5 Accuracy | ≥ 70% | Substantial agreement with expert performance |

All thresholds have been set according to existing literature on fine-grained skin disease classification [1, 2, 9, 42, 53], and they must be achieved with 95% confidence intervals. Due to the lack of works reporting Top-K accuracy metrics on both clinical and dermoscopy images, our thresholds were determined by defining the Top-1 accuracy threshold (50%) based on the existing literature on clinical image analysis [1, 3, 9, 52], and increasing it in 10% steps.

The resulting thresholds offer a realistic expectation of performance in this extremely long-tailed, fine-grained classification problem, which goes beyond the typical skin lesion classification scenario.

Requirements:

- Implement image analysis models capable of ICD classification [15].

- Output normalized probability distributions (sum = 100%).

- Demonstrate performance above top-1, top-3, and top-5 thresholds in independent test data.

- Validate the model on an independent and diverse test dataset to ensure generalizability across skin types, age groups, and imaging conditions.

Binary Indicator Endpoints and Requirements

Performance of binary indicators is evaluated using AUC (Area Under the ROC Curve) against dermatologists' consensus labels.

| AUC Score | Agreement Category | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

< 0.70 | Poor | Not acceptable for clinical use |

0.70 - 0.79 | Fair | Below acceptance threshold |

0.80 - 0.89 | Good | Meets acceptance threshold |

0.90 - 0.95 | Excellent | High robustness |

> 0.95 | Outstanding | Near-expert level performance |

Each binary indicator must achieve AUC ≥ 0.80 with 95% confidence intervals, validated against independent datasets including malignant, premalignant, associated to malignancy, pigmented, urgent, and high-priority referral cases.

Despite the existing literature has consistently reported malignancy prediction AUCs beyond 0.90 [1, 3, 4, 5, 9], we strongly believe such performance levels are influenced by small test dataset size and, to some extent, data overfitting. In contrast, we set a goal of 0.80 AUC for all binary indicators in our large, more diverse and highly heterogeneous test set to demonstrate successful model generalization beyond a specific dataset's characteristics.

Requirements:

- Implement all binary indicators:

- Malignant

- Pre-malignant

- Associated with malignancy

- Pigmented lesion

- Urgent referral (≤48h)

- High-priority referral (≤2 weeks)

- Define and document the dermatologist-validated mapping matrix .

- Provide outputs consistent with clinical triage guidelines (urgent and high-priority referrals).

- Validate performance on diverse and independent datasets representing both common and rare conditions, as well as positive and negative cases for each indicator.

- Validate performance across skin types, age groups and imaging conditions.

- Ensure ≥0.80 AUC across all indicators with reporting of 95% confidence intervals.

Erythema Intensity Quantification

Model Classification: 🔬 Clinical Model

Description

A deep learning model ingests an image of a skin lesion and outputs a probability vector:

where each (for ) corresponds to the model’s softmax-normalized probability that the erythema intensity belongs to ordinal category (ranging from minimal to maximal erythema).

Although the outputs are numeric, they represent ordinal categorical values. To derive a continuous erythema severity score , a weighted expected value is computed:

This post-processing step ensures that the prediction reflects a continuous probability distribution rather than only the most likely class, yielding a more stable and clinically interpretable severity score.

Objectives

- Support healthcare professionals in the assessment of erythema severity by providing an objective, quantitative measure.

- Reduce inter-observer and intra-observer variability, which is well documented in erythema scoring scales (e.g., Clinician’s Erythema Assessment [CEA] interrater ICC ≈ 0.60, weighted κ ≈ 0.69) [21].

- Ensure reproducibility and robustness across imaging conditions (e.g., brightness, contrast, device type).

- Facilitate standardized evaluation in clinical practice and research, particularly in multi-center studies where subjective scoring introduces variability.

- Enable calculation of severity scores for conditions where erythema quantification is a key component, such as PASI (Psoriasis Area and Severity Index), EASI (Eczema Area and Severity Index), SCORAD (SCORing Atopic Dermatitis), GPPGA (Generalized Pustular Psoriasis Global Assessment), and PPPASI (Palmoplantar Pustular Psoriasis Area and Severity Index).

Justification (Clinical Evidence):

- Studies have shown that CNN-based models can achieve dermatologist-level accuracy in erythema scoring (e.g., ResNet models reached ~99% accuracy in erythema detection under varying conditions) [22, 23].

- Automated erythema quantification has demonstrated reduced variability compared to human raters in tasks such as Minimum Erythema Dose (MED) and SPF index assessments [24].

- Clinical scales such as the CEA, though widely used, suffer from subjectivity; integrating AI quantification can strengthen reliability and reproducibility [21].

Endpoints and Requirements

Performance is evaluated using the Relative Mean Absolute Error (RMAE), defined as the Mean Absolute Error normalized by the full ordinal range (maximum = 9).

| Metric | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| RMAE | ≤ 14% | Algorithm outputs are consistent with expert consensus (RMAE ≤ 14%), with performance superior to inter-observer variability. |

All thresholds must be achieved with 95% confidence intervals.

Requirements:

- Output a normalized probability distribution across 10 ordinal categories (softmax output, sum = 1).

- Convert probability outputs into a continuous score using the weighted expected value formula:

- Demonstrate RMAE ≤ 14%, outperforming the average expert-to-expert variability.

- Report all metrics with 95% confidence intervals.

- Validate the model on an independent and diverse test dataset to ensure generalizability, including:

- Various Fitzpatrick skin types (I-VI)

- Multiple anatomical sites (scalp, trunk, extremities, intertriginous areas)

- Different imaging devices and conditions (including varying angles and lighting)

- Disease conditions including psoriasis, eczema, seborrheic dermatitis, and other inflammatory dermatoses

- Range of severity levels from minimal to severe erythema

Desquamation Intensity Quantification

Model Classification: 🔬 Clinical Model

Description

A deep learning model ingests an image of a skin lesion and outputs a probability vector:

where each (for ) corresponds to the model's softmax-normalized probability that the desquamation intensity belongs to ordinal category (ranging from minimal to maximal scaling/peeling).

Although the outputs are numeric, they represent ordinal categorical values. To derive a continuous desquamation severity score , a weighted expected value is computed:

This post-processing step ensures that the prediction reflects a continuous probability distribution rather than only the most likely class, yielding a more stable and clinically interpretable severity score.

Objectives

- Support healthcare professionals in assessing desquamation severity by providing an objective, quantitative measure.

- Reduce inter-observer and intra-observer variability, which is well documented in visual scaling/peeling assessments in dermatology.

- Ensure reproducibility and robustness across imaging conditions (illumination, device type, contrast).

- Facilitate standardized evaluation in clinical practice and research, especially in multi-center trials where variability in subjective desquamation scoring reduces reliability.

- Enable calculation of severity scores for conditions where desquamation quantification is a key component, such as PASI (Psoriasis Area and Severity Index), GPPGA (Generalized Pustular Psoriasis Global Assessment), and PPPASI (Palmoplantar Pustular Psoriasis Area and Severity Index).

Justification (Clinical Evidence):

- Studies in dermatology have shown moderate to substantial interrater variability in desquamation scoring (e.g., psoriasis and radiation dermatitis grading) with κ values often

<0.70, with some studies reporting ICC values as low as 0.45-0.60 [37, 38]. - The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) includes scaling as one of three cardinal signs, but manual assessment shows significant variability, particularly in distinguishing between adjacent severity grades [39].

- Automated computer vision and CNN-based methods have demonstrated high accuracy in texture and scaling detection, achieving accuracies >85% and often surpassing human raters in consistency [39, 40].

- Objective desquamation quantification can improve reproducibility in psoriasis PASI scoring and oncology trials, where scaling/desquamation is a critical endpoint but prone to subjectivity, with automated methods showing correlation (r > 0.80) with expert consensus [37].

- Deep learning texture analysis has proven particularly effective for subtle scaling patterns that may be missed or inconsistently graded by visual inspection alone [40].

- Studies in radiation dermatitis assessment show that automated desquamation grading reduces inter-observer variability by 30-40% compared to traditional visual scoring [38].

Endpoints and Requirements

Performance is evaluated using the Relative Mean Absolute Error (RMAE), defined as the Mean Absolute Error normalized by the full ordinal range (maximum = 9).

| Metric | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| RMAE | ≤ 17% | Algorithm outputs are consistent with expert consensus (RMAE ≤ 17%), with performance superior to inter-observer variability. |

All thresholds must be achieved with 95% confidence intervals.

Requirements:

- Output a normalized probability distribution across 10 ordinal categories (softmax output, sum = 1).

- Convert probability outputs into a continuous score using the weighted expected value formula:

- Demonstrate RMAE ≤ 17%, outperforming the average expert-to-expert variability.

- Report all metrics with 95% confidence intervals.

- Validate the model on an independent and diverse test dataset including:

- Various Fitzpatrick skin types (I-VI)

- Multiple anatomical sites (scalp, trunk, extremities, intertriginous areas)

- Different imaging devices and conditions (including varying angles and lighting)

- Disease conditions including psoriasis, eczema, seborrheic dermatitis, and other inflammatory dermatoses

- Range of severity levels from minimal to severe desquamation

- Ensure outputs are compatible with automated PASI calculation when combined with erythema, induration, and body surface area assessment.

Induration Intensity Quantification

Model Classification: 🔬 Clinical Model

Description

A deep learning model ingests an image of a skin lesion and outputs a probability vector:

where each (for ) corresponds to the model's softmax-normalized probability that the induration intensity belongs to ordinal category (ranging from minimal to maximal induration/plaque thickness).

Although the outputs are numeric, they represent ordinal categorical values. To derive a continuous induration severity score , a weighted expected value is computed:

This post-processing step ensures that the prediction reflects a continuous probability distribution rather than only the most likely class, yielding a more stable and clinically interpretable severity score.

Objectives

- Support healthcare professionals in assessing induration (plaque thickness) severity by providing an objective, quantitative measure.

- Reduce inter-observer and intra-observer variability, which is well documented in visual induration assessments in dermatology.

- Ensure reproducibility and robustness across imaging conditions (illumination, angle, device type, contrast).

- Facilitate standardized evaluation in clinical practice and research, especially in multi-center trials where variability in subjective induration scoring reduces reliability.

- Support calculation of PASI score, as induration (plaque thickness) is one of the three key components of the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index.

Justification (Clinical Evidence):

- Studies in dermatology have shown moderate to substantial interrater variability in induration scoring (e.g., psoriasis and other inflammatory dermatoses) with κ values often

<0.70, with reported ICC values ranging from 0.50-0.65 for plaque thickness assessment [37]. - The Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) includes induration/infiltration as one of three cardinal signs, with plaque thickness being a key indicator of disease severity and treatment response [39].

- Visual assessment of induration is particularly challenging as it relies on tactile and visual cues that are difficult to standardize, leading to significant inter-observer disagreement, especially for intermediate severity levels [37].

- Automated computer vision and CNN-based methods have demonstrated high accuracy in detecting plaque elevation and thickness, using shadow analysis, depth estimation, and texture features to achieve performance comparable to expert palpation-informed visual assessment [39, 40].

- Objective induration quantification can improve reproducibility in clinical trials and routine care, where induration is a critical endpoint but prone to subjectivity, with automated methods showing strong correlation (r > 0.75) with expert consensus and high-frequency ultrasound measurements [37].

- Studies using advanced imaging techniques (e.g., optical coherence tomography) for validation have shown that AI-based induration assessment from standard photographs can achieve accuracy within 15-20% of reference measurements [40].

- Induration assessment is particularly important for treatment monitoring, as changes in plaque thickness are early indicators of therapeutic response, often preceding changes in erythema or scaling [39].

Endpoints and Requirements

Performance is evaluated using the Relative Mean Absolute Error (RMAE), defined as the Mean Absolute Error normalized by the full ordinal range (maximum = 9).

| Metric | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| RMAE | ≤ 17% | Algorithm outputs are consistent with expert consensus (RMAE ≤ 17%), with performance superior to inter-observer variability. |

All thresholds must be achieved with 95% confidence intervals.

Requirements:

- Output a normalized probability distribution across 10 ordinal categories (softmax output, sum = 1).

- Convert probability outputs into a continuous score using the weighted expected value formula:

- Demonstrate RMAE ≤ 17%, outperforming the average expert-to-expert variability.

- Report all metrics with 95% confidence intervals.

- Validate the model on an independent and diverse test dataset including:

- Various Fitzpatrick skin types (I-VI)

- Multiple anatomical sites (scalp, trunk, extremities, intertriginous areas)

- Different imaging devices and conditions (including varying angles and lighting)

- Disease conditions including psoriasis, eczema, lichen planus, and other inflammatory dermatoses with plaque formation

- Range of severity levels from minimal to severe induration/plaque thickness

- Ensure outputs are compatible with automated PASI calculation when combined with erythema, desquamation, and body surface area assessment.

Pustule Intensity Quantification

Model Classification: 🔬 Clinical Model

Description

A deep learning model ingests an image of a skin lesion and outputs a probability vector:

where each (for ) corresponds to the model's softmax-normalized probability that the pustule intensity belongs to ordinal category (ranging from minimal to maximal pustulation).

Although the outputs are numeric, they represent ordinal categorical values. To derive a continuous pustule severity score , a weighted expected value is computed:

This post-processing step ensures that the prediction reflects a continuous probability distribution rather than only the most likely class, yielding a more stable and clinically interpretable severity score.

Objectives

- Support healthcare professionals in the assessment of pustule severity by providing an objective, quantitative measure.

- Reduce inter-observer and intra-observer variability, which is well documented in pustule scoring for conditions such as pustular psoriasis and acne (interrater ICC ≈ 0.55-0.70, κ ≈ 0.60-0.75).

- Ensure reproducibility and robustness across imaging conditions (e.g., brightness, contrast, device type, anatomical location).

- Facilitate standardized evaluation in clinical practice and research, particularly in multi-center studies where subjective pustule scoring introduces variability.

- Enable calculation of severity scores for conditions where pustule quantification is a key component, such as pustular psoriasis (PPPASI - Palmoplantar Pustular Psoriasis Area and Severity Index), generalized pustular psoriasis (GPPGA - Generalized Pustular Psoriasis Global Assessment), and acne vulgaris.

Justification (Clinical Evidence):

- Studies have shown that CNN-based models can achieve dermatologist-level accuracy in pustule detection and scoring, with accuracies exceeding 85% in distinguishing pustules from papules and other inflammatory lesions [27, 28, 118].

- Automated pustule quantification has demonstrated reduced variability compared to human raters in pustular dermatosis assessment, with improved inter-observer reliability [29, 118].

- Clinical scales for pustular conditions such as PPPASI and GPPGA rely on pustule counting and severity grading, but suffer from subjectivity; integrating AI quantification can strengthen reliability and reproducibility [39].

- Pustule assessment is particularly challenging due to the need to distinguish pustules from vesicles, papules, and crusted lesions, leading to significant inter-observer variation [112, 113].

Endpoints and Requirements

Performance is evaluated using the Relative Mean Absolute Error (RMAE), defined as the Mean Absolute Error normalized by the full ordinal range (maximum = 9).

| Metric | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| RMAE | ≤ 30% | Algorithm outputs are consistent with expert consensus (RMAE ≤ 30%), with performance superior to inter-observer variability. |

All thresholds must be achieved with 95% confidence intervals.

Requirements:

- Output a normalized probability distribution across 10 ordinal categories (softmax output, sum = 1).

- Convert probability outputs into a continuous score using the weighted expected value formula:

- Demonstrate RMAE ≤ 30%, outperforming the average expert-to-expert variability.

- Report all metrics with 95% confidence intervals.

- Validate the model on an independent and diverse test dataset including:

- Various Fitzpatrick skin types (I-VI)

- Multiple anatomical sites (palms, soles, trunk, extremities, scalp, intertriginous areas)

- Different imaging devices and conditions (including varying angles and lighting)

- Disease conditions including pustular psoriasis (palmoplantar and generalized), acne vulgaris, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), subcorneal pustular dermatosis, and other pustular dermatoses

- Range of severity levels from minimal to severe pustulation

- Various pustule sizes and densities

- Ensure outputs are compatible with automated severity scoring for conditions where pustule assessment is a key component (e.g., PPPASI, GPPGA, acne grading systems).

Crusting Intensity Quantification

Model Classification: 🔬 Clinical Model

Description

A deep learning model ingests an image of a skin lesion and outputs a probability vector:

where each (for ) corresponds to the model's softmax-normalized probability that the crusting intensity belongs to ordinal category (ranging from minimal to maximal crusting severity).

Although the outputs are numeric, they represent ordinal categorical values. To derive a continuous crusting severity score , a weighted expected value is computed:

This post-processing step ensures that the prediction reflects a continuous probability distribution rather than only the most likely class, yielding a more stable and clinically interpretable severity score.

Objectives

- Support healthcare professionals in assessing crusting severity by providing an objective, quantitative measure.

- Reduce inter-observer and intra-observer variability, which is well documented in visual crusting assessments in dermatology.

- Ensure reproducibility and robustness across imaging conditions (illumination, device type, contrast).

- Facilitate standardized evaluation in clinical practice and research, especially in multi-center trials where variability in subjective crusting scoring reduces reliability.

- Support comprehensive dermatitis assessment, as crusting is a key component in severity scoring systems such as EASI and SCORAD for atopic dermatitis and other inflammatory conditions.

Justification (Clinical Evidence):

- Studies in dermatology have shown moderate to substantial interrater variability in crusting scoring (e.g., atopic dermatitis, impetigo, psoriasis, and eczematous conditions) with κ values often

<0.70, with some studies reporting ICC values as low as 0.40-0.65 [37]. - Crusting assessment is particularly challenging because it represents secondary changes that vary in color, thickness, and distribution, leading to inconsistent grading between observers [38].

- Automated computer vision and CNN-based methods have demonstrated high accuracy in texture and crust detection, achieving accuracies >85% in identifying and grading crusted lesions, often surpassing human raters in consistency [39, 40].

- Objective crusting quantification can improve reproducibility in clinical trials and routine care, where crusting is a critical endpoint but prone to subjectivity, with automated methods showing correlation (r > 0.78) with expert consensus [37].

- Deep learning texture analysis has proven particularly effective for distinguishing crust from scale and other surface changes, which may appear similar but have different clinical implications [40].

- In atopic dermatitis assessment, crusting severity correlates with disease activity and infection risk, making accurate quantification important for treatment decisions [38].

Endpoints and Requirements

Performance is evaluated using the Relative Mean Absolute Error (RMAE), defined as the Mean Absolute Error normalized by the full ordinal range (maximum = 9).

| Metric | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| RMAE | ≤ 20% | Algorithm outputs are consistent with expert consensus (RMAE ≤ 20%), with performance superior to inter-observer variability. |

All thresholds must be achieved with 95% confidence intervals.

Requirements:

- Output a normalized probability distribution across 10 ordinal categories (softmax output, sum = 1).

- Convert probability outputs into a continuous score using the weighted expected value formula:

- Demonstrate RMAE ≤ 20%, outperforming the average expert-to-expert variability.

- Report all metrics with 95% confidence intervals.

- Validate the model on an independent and diverse test dataset including:

- Various Fitzpatrick skin types (I-VI)

- Multiple anatomical sites (face, scalp, trunk, extremities, intertriginous areas)

- Different imaging devices and conditions (including varying angles and lighting)

- Disease conditions including atopic dermatitis, impetigo, psoriasis, eczema, and other inflammatory dermatoses

- Range of severity levels from minimal to severe crusting

- Various crust types (serous, hemorrhagic, purulent)

- Ensure outputs are compatible with automated severity scoring for conditions where crusting is a key component (e.g., EASI for atopic dermatitis, SCORAD, wound assessment scales).

Xerosis Intensity Quantification

Model Classification: 🔬 Clinical Model

Description

A deep learning model ingests an image of a skin lesion and outputs a probability vector:

where each (for ) corresponds to the model's softmax-normalized probability that the xerosis (dry skin) intensity belongs to ordinal category (ranging from minimal to maximal xerosis severity).

Although the outputs are numeric, they represent ordinal categorical values. To derive a continuous xerosis severity score , a weighted expected value is computed:

This post-processing step ensures that the prediction reflects a continuous probability distribution rather than only the most likely class, yielding a more stable and clinically interpretable severity score.

Objectives

- Support healthcare professionals in assessing xerosis (dry skin) severity by providing an objective, quantitative measure.

- Reduce inter-observer and intra-observer variability, which is particularly challenging in xerosis assessment due to its complex visual and textural manifestations.

- Ensure reproducibility and robustness across imaging conditions (illumination, device type, contrast, magnification).

- Facilitate standardized evaluation in clinical practice and research, especially in multi-center trials where variability in subjective xerosis scoring reduces reliability.

- Support comprehensive skin barrier assessment, as xerosis is a fundamental sign of impaired skin barrier function in conditions such as atopic dermatitis, ichthyosis, and aging skin.

Justification (Clinical Evidence):

- Clinical studies have demonstrated significant inter-observer variability in xerosis assessment, with reported κ values ranging from 0.35 to 0.65 for visual scoring systems, with some studies showing even lower reliability (ICC 0.30-0.50) for subtle xerosis [37, 38].

- The Overall Dry Skin Score (ODS) and similar xerosis scales are widely used but show limited reproducibility between assessors, particularly for intermediate severity grades [40].

- Deep learning methods using texture analysis have shown superior performance in skin surface assessment, achieving accuracies >90% in detecting and grading xerosis patterns, particularly when analyzing fine-scale texture features [39].

- Recent validation studies of AI-based xerosis assessment have demonstrated strong correlation with objective instrumentation: corneometer measurements (r > 0.85), transepidermal water loss (TEWL) measurements (r > 0.75), and capacitance measurements [40].

- Xerosis severity correlates with skin barrier dysfunction and predicts disease flares in atopic dermatitis, with objective quantification enabling early intervention before clinical exacerbation [38].

- Automated xerosis grading reduces assessment time by 40-50% while improving consistency, particularly beneficial in large-scale screening or longitudinal monitoring [39].

- Texture-based deep learning features can distinguish between xerosis and normal skin surface variations that may be confounded in manual assessment, improving specificity [40].

Endpoints and Requirements

Performance is evaluated using the Relative Mean Absolute Error (RMAE), defined as the Mean Absolute Error normalized by the full ordinal range (maximum = 9).

| Metric | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| RMAE | ≤ 20% | Algorithm outputs are consistent with expert consensus (RMAE ≤ 20%), with performance superior to inter-observer variability. |

All thresholds must be achieved with 95% confidence intervals.

Requirements:

- Output a normalized probability distribution across 10 ordinal categories (softmax output, sum = 1).

- Convert probability outputs into a continuous score using the weighted expected value formula:

- Demonstrate RMAE ≤ 20%, outperforming the average expert-to-expert variability.

- Report all metrics with 95% confidence intervals.

- Validate the model on an independent and diverse test dataset including:

- Various Fitzpatrick skin types (I-VI)

- Multiple anatomical sites (face, hands, lower legs, trunk—sites with varying baseline dryness)

- Different imaging devices and conditions (including macro photography for texture detail, or varying angles and lighting)

- Disease conditions including atopic dermatitis, ichthyosis, psoriasis, aging skin, and environmental xerosis

- Range of severity levels from minimal to severe xerosis

- Seasonal variations (winter vs. summer xerosis patterns)

- Ensure outputs are compatible with automated severity scoring for conditions where xerosis is a key component (e.g., EASI for atopic dermatitis, SCORAD, xerosis-specific scales).

- Provide correlation analysis with objective measurements (corneometer, TEWL) when validation data includes instrumental assessments.

Swelling Intensity Quantification

Model Classification: 🔬 Clinical Model

Description

A deep learning model ingests an image of a skin lesion and outputs a probability vector:

where each (for ) corresponds to the model's softmax-normalized probability that the swelling (edema) intensity belongs to ordinal category (ranging from minimal to maximal swelling severity).

Although the outputs are numeric, they represent ordinal categorical values. To derive a continuous swelling severity score , a weighted expected value is computed:

This post-processing step ensures that the prediction reflects a continuous probability distribution rather than only the most likely class, yielding a more stable and clinically interpretable severity score.

Objectives

- Support healthcare professionals in assessing swelling/edema severity by providing an objective, quantitative measure from 2D images.

- Reduce inter-observer and intra-observer variability, which is especially challenging in swelling assessment due to its three-dimensional nature and subtle manifestations.

- Ensure reproducibility and robustness across imaging conditions (illumination, angle, device type, distance).

- Facilitate standardized evaluation in clinical practice and research, especially in multi-center trials where variability in subjective edema scoring reduces reliability.

- Support comprehensive inflammatory assessment, as swelling is a cardinal sign in conditions such as atopic dermatitis, urticaria, angioedema, and other inflammatory dermatoses.

Justification (Clinical Evidence):

- Clinical studies show significant variability in visual edema assessment, with interrater reliability coefficients (ICC) ranging from 0.42 to 0.68 for traditional scoring methods, particularly for mild to moderate edema [37, 38].

- Visual assessment of swelling is inherently challenging because it requires 3D assessment from 2D images, relying on indirect cues such as skin texture changes, shadow patterns, and loss of normal skin markings [39].

- Three-dimensional analysis using deep learning has demonstrated superior accuracy (>85%) in detecting and grading tissue swelling compared to conventional 2D visual assessment methods, utilizing shadow analysis and surface contour estimation [39].

- Recent studies have validated AI-based swelling quantification against gold standard volumetric measurements (water displacement, 3D scanning), showing strong correlation (r > 0.80) despite using only 2D photographic input [40].

- Computer vision techniques incorporating shadow analysis, surface normal estimation, and texture pattern recognition have shown promise in objective edema assessment, with validation studies reporting accuracy improvements of 25-30% over traditional visual scoring [39].

- In atopic dermatitis, swelling severity correlates with acute inflammatory activity and response to anti-inflammatory treatment, making accurate assessment important for monitoring [38].

- Automated swelling quantification can detect subtle changes that may be missed by visual assessment, enabling earlier detection of treatment response or disease flare [40].

Endpoints and Requirements

Performance is evaluated using the Relative Mean Absolute Error (RMAE), defined as the Mean Absolute Error normalized by the full ordinal range (maximum = 9).

| Metric | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| RMAE | ≤ 20% | Algorithm outputs are consistent with expert consensus (RMAE ≤ 20%), with performance superior to inter-observer variability. |

All thresholds must be achieved with 95% confidence intervals.

Requirements:

- Output a normalized probability distribution across 10 ordinal categories (softmax output, sum = 1).

- Convert probability outputs into a continuous score using the weighted expected value formula:

- Demonstrate RMAE ≤ 20%, outperforming the average expert-to-expert variability.

- Report all metrics with 95% confidence intervals.

- Validate the model on an independent and diverse test dataset including:

- Various Fitzpatrick skin types (I-VI)

- Multiple anatomical sites (face, extremities, trunk—sites with different baseline tissue compliance)

- Different imaging devices and conditions (standardized angles when possible)

- Disease conditions including atopic dermatitis, urticaria, angioedema, contact dermatitis, and other inflammatory dermatoses with edematous component

- Range of severity levels from minimal to severe swelling

- Acute vs. chronic swelling patterns

- Document imaging recommendations for optimal swelling assessment (e.g., consistent angle, standardized distance, lighting to enhance shadow visualization).

- Ensure outputs are compatible with automated severity scoring for conditions where swelling is a key component (e.g., EASI for atopic dermatitis, SCORAD, urticaria activity scores).

Oozing Intensity Quantification

Model Classification: 🔬 Clinical Model

Description

A deep learning model ingests an image of a skin lesion and outputs a probability vector:

where each (for ) corresponds to the model's softmax-normalized probability that the oozing (exudation) intensity belongs to ordinal category (ranging from minimal to maximal oozing severity).

Although the outputs are numeric, they represent ordinal categorical values. To derive a continuous oozing severity score , a weighted expected value is computed:

This post-processing step ensures that the prediction reflects a continuous probability distribution rather than only the most likely class, yielding a more stable and clinically interpretable severity score.

Objectives

- Support healthcare professionals in assessing oozing/exudate severity by providing an objective, quantitative measure.

- Reduce inter-observer and intra-observer variability, which is particularly challenging in oozing assessment due to the dynamic nature of exudates and varying light reflectance.

- Ensure reproducibility and robustness across imaging conditions (illumination, moisture levels, device type, time since onset).

- Facilitate standardized evaluation in clinical practice and research, especially in acute inflammatory dermatoses and wound care where exudate quantification is crucial for monitoring.

- Support infection risk assessment, as oozing characteristics (serous vs. purulent, volume) correlate with likelihood of secondary infection in inflammatory skin conditions.

Justification (Clinical Evidence):

- Clinical studies demonstrate substantial variability in visual exudate assessment, with reported κ values of 0.31-0.58 for traditional exudate scoring systems in dermatology and wound care [37, 38].

- Oozing assessment is particularly challenging due to its temporal variability—exudate may be present at varying intensities throughout the day or may have dried between episodes, leading to inconsistent grading [38].

- Advanced image processing techniques combining RGB analysis, reflectance modeling, and texture features have achieved >85% accuracy in detecting and grading exudate levels in both acute dermatitis and wound contexts [39].

- Validation studies comparing AI-based exudate assessment with absorbent pad weighing (in wound care) showed strong correlation (r > 0.82), demonstrating agreement with objective measurement methods [40].

- Multi-spectral imaging analysis has demonstrated improved detection of subtle exudate variations and differentiation between serous and purulent exudate, with sensitivity improvements of 30-40% over standard visual assessment [39].

- In atopic dermatitis, oozing severity is a key indicator of acute flare and secondary infection, with presence of oozing increasing infection probability 3-4 fold [38].

- Oozing is a key component of EASI and SCORAD assessment in atopic dermatitis, and its accurate quantification improves overall severity score reliability [37].

Endpoints and Requirements

Performance is evaluated using the Relative Mean Absolute Error (RMAE), defined as the Mean Absolute Error normalized by the full ordinal range (maximum = 9).

| Metric | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| RMAE | ≤ 20% | Algorithm outputs are consistent with expert consensus (RMAE ≤ 20%), with performance superior to inter-observer variability. |

All thresholds must be achieved with 95% confidence intervals.

Requirements:

- Output a normalized probability distribution across 10 ordinal categories (softmax output, sum = 1).

- Convert probability outputs into a continuous score using the weighted expected value formula:

- Demonstrate RMAE ≤ 20%, outperforming the average expert-to-expert variability.

- Report all metrics with 95% confidence intervals.

- Validate the model on an independent and diverse test dataset including:

- Various Fitzpatrick skin types (I-VI)

- Multiple anatomical sites (face, intertriginous areas, extremities)

- Different imaging devices and conditions

- Disease conditions including acute atopic dermatitis, impetigo, infected eczema, bullous disorders, and other conditions with exudative component

- Range of severity levels from minimal to severe oozing

- Different exudate types (serous, serosanguinous, purulent) when distinguishable

- Fresh vs. dried exudate patterns

- Document timing recommendations for optimal oozing assessment (e.g., assessment window relative to lesion cleaning).

- Ensure outputs are compatible with automated severity scoring for conditions where oozing is a key component (e.g., EASI for atopic dermatitis, SCORAD, wound assessment scales).

Excoriation Intensity Quantification

Model Classification: 🔬 Clinical Model

Description

A deep learning model ingests an image of a skin lesion and outputs a probability vector:

where each (for ) corresponds to the model's softmax-normalized probability that the excoriation intensity belongs to ordinal category (ranging from minimal to maximal excoriation severity).

Although the outputs are numeric, they represent ordinal categorical values. To derive a continuous excoriation severity score , a weighted expected value is computed:

This post-processing step ensures that the prediction reflects a continuous probability distribution rather than only the most likely class, yielding a more stable and clinically interpretable severity score.

Objectives

- Support healthcare professionals in assessing excoriation (scratch damage) severity by providing an objective, quantitative measure.

- Reduce inter-observer and intra-observer variability, which is particularly challenging in excoriation assessment due to the varied appearance and distribution of scratch marks.

- Ensure reproducibility and robustness across imaging conditions (illumination, angle, device type).

- Facilitate standardized evaluation in clinical practice and research, especially in conditions where excoriation is a key indicator of disease severity and pruritus intensity.

- Support pruritus assessment, as excoriation serves as an objective marker of scratching behavior, which correlates with pruritus severity in atopic dermatitis and other pruritic conditions.

Justification (Clinical Evidence):

- Studies of atopic dermatitis scoring systems show moderate interrater reliability for excoriation assessment, with ICC values ranging from 0.41-0.63, reflecting the subjective nature of grading scratch marks [37].

- Excoriation assessment is challenging because scratch patterns vary widely in linear density, depth, healing stage, and may overlap with other lesions, leading to inconsistent grading [38].

- Computer vision techniques incorporating linear feature detection, edge analysis, and pattern recognition have achieved >80% accuracy in identifying and grading excoriation patterns [39].

- Recent validation studies comparing automated excoriation scoring with standardized photography assessment showed substantial agreement (κ > 0.75) with expert consensus [40].

- Machine learning approaches have demonstrated a 25% improvement in consistency of excoriation grading compared to traditional visual scoring methods, particularly for intermediate severity levels [39].

- Excoriation severity is a key component of EASI and SCORAD in atopic dermatitis, and correlates strongly with patient-reported pruritus scores (r = 0.65-0.75), making it a valuable objective marker [37].

- Longitudinal tracking of excoriation severity can detect early treatment response to anti-pruritic interventions before subjective pruritus scores change [38].

- Excoriation presence and severity are associated with sleep disturbance and quality of life impairment in pruritic dermatoses, emphasizing clinical importance of accurate quantification [37].

Endpoints and Requirements

Performance is evaluated using the Relative Mean Absolute Error (RMAE), defined as the Mean Absolute Error normalized by the full ordinal range (maximum = 9).

| Metric | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| RMAE | ≤ 14% | Algorithm outputs are consistent with expert consensus (RMAE ≤ 14%), with performance superior to inter-observer variability. |

All thresholds must be achieved with 95% confidence intervals.

Requirements:

- Output a normalized probability distribution across 10 ordinal categories (softmax output, sum = 1).

- Convert probability outputs into a continuous score using the weighted expected value formula:

- Demonstrate RMAE ≤ 14%, outperforming the average expert-to-expert variability.

- Report all metrics with 95% confidence intervals.

- Validate the model on an independent and diverse test dataset including:

- Various Fitzpatrick skin types (I-VI)—excoriation visibility varies with skin tone

- Multiple anatomical sites (face, trunk, extremities, particularly flexural areas in atopic dermatitis)

- Different imaging devices and conditions

- Disease conditions including atopic dermatitis, prurigo nodularis, lichen simplex chronicus, neurotic excoriations, and other pruritic dermatoses

- Range of severity levels from minimal to severe excoriation

- Different healing stages (acute, subacute, healed with residual marks)

- Linear vs. punctate excoriation patterns

- Ensure outputs are compatible with automated severity scoring for conditions where excoriation is a key component (e.g., EASI for atopic dermatitis, SCORAD, prurigo scoring systems).

Lichenification Intensity Quantification

Model Classification: 🔬 Clinical Model

Description

A deep learning model ingests an image of a skin lesion and outputs a probability vector:

where each (for ) corresponds to the model's softmax-normalized probability that the lichenification intensity belongs to ordinal category (ranging from minimal to maximal lichenification severity).

Although the outputs are numeric, they represent ordinal categorical values. To derive a continuous lichenification severity score , a weighted expected value is computed:

This post-processing step ensures that the prediction reflects a continuous probability distribution rather than only the most likely class, yielding a more stable and clinically interpretable severity score.

Objectives

- Support healthcare professionals in assessing lichenification (skin thickening with accentuated skin markings) severity by providing an objective, quantitative measure.

- Reduce inter-observer and intra-observer variability, which is particularly challenging due to the subtle gradations in skin texture and thickness.

- Ensure reproducibility and robustness across imaging conditions (illumination, angle, magnification, distance).

- Facilitate standardized evaluation in clinical practice and research, especially in chronic conditions where lichenification is a key indicator of disease chronicity and chronicity-related treatment resistance.

- Support chronicity assessment, as lichenification represents chronic rubbing/scratching and is a marker of established, potentially treatment-resistant dermatosis requiring more aggressive intervention.

Justification (Clinical Evidence):

- Analysis of scoring systems for chronic skin conditions shows significant variability in lichenification assessment, with reported κ values of 0.45-0.70, reflecting difficulty in standardizing texture and thickness grading [37].

- Lichenification assessment is particularly challenging because it requires evaluating subtle changes in skin surface texture, accentuation of normal skin lines, and thickness—features that are difficult to quantify visually and may require tactile assessment [38].

- Advanced texture analysis algorithms have demonstrated superior detection of lichenified patterns, achieving accuracy rates >85% in identifying skin thickening and texture changes characteristic of lichenification [39].

- Validation studies comparing AI-based lichenification assessment with high-frequency ultrasound measurements (20-100 MHz) showed strong correlation (r > 0.78) with objective epidermal and dermal thickness measurements [40].

- Deep learning approaches incorporating depth estimation, shadow analysis, and fine-scale texture pattern recognition have shown 35% improvement in consistency compared to traditional visual scoring methods [39].

- Lichenification severity is a key component of EASI and SCORAD in atopic dermatitis, and its presence indicates chronic disease requiring intensified treatment, including consideration of systemic therapy [37].

- Lichenification correlates with treatment resistance—lichenified lesions respond more slowly to topical corticosteroids and require longer treatment duration [38].

- In lichen simplex chronicus, lichenification severity predicts time to resolution and recurrence risk, making accurate assessment important for prognosis [40].

Endpoints and Requirements

Performance is evaluated using the Relative Mean Absolute Error (RMAE), defined as the Mean Absolute Error normalized by the full ordinal range (maximum = 9).

| Metric | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| RMAE | ≤ 17% | Algorithm outputs are consistent with expert consensus (RMAE ≤ 17%), with performance superior to inter-observer variability. |

All thresholds must be achieved with 95% confidence intervals.

Requirements:

- Output a normalized probability distribution across 10 ordinal categories (softmax output, sum = 1).

- Convert probability outputs into a continuous score using the weighted expected value formula:

- Demonstrate RMAE ≤ 17%, outperforming the average expert-to-expert variability.

- Report all metrics with 95% confidence intervals.

- Validate the model on an independent and diverse test dataset including:

- Various Fitzpatrick skin types (I-VI) — lichenification appearance varies with pigmentation

- Multiple anatomical sites (nape of neck, ankles, wrists, antecubital/popliteal fossae—common lichenification sites)

- Different imaging devices and conditions (macro photography beneficial for texture detail)

- Disease conditions including chronic atopic dermatitis, lichen simplex chronicus, prurigo nodularis, chronic contact dermatitis, and other chronic pruritic dermatoses

- Range of severity levels from minimal to severe lichenification

- Early vs. advanced lichenification (subtle accentuation vs. pronounced thickening)

- Document imaging recommendations for optimal lichenification assessment (e.g., lighting angle to enhance skin markings, appropriate magnification for texture detail).

- Ensure outputs are compatible with automated severity scoring for conditions where lichenification is a key component (e.g., EASI for atopic dermatitis, SCORAD, lichen simplex chronicus severity scores).

- Provide correlation analysis with objective measurements (ultrasound thickness, tactile assessment) when validation data includes instrumental or palpation-based assessments.

Wound Characteristic Assessment

Models Classification: 🔬 Clinical Model

Description

A set of deep learning classification models, and a regression model process images of wounds and output multiple predictions related to wound staging and morphological characteristics. Together, these models provide a comprehensive, standardized assessment of wound condition.

The system comprises:

- Stage Classification Model – predicts a categorical output corresponding to the wound stage (0–4).

- Intensity Regression Model – predicts a continuous score representing overall wound intensity on a 0–19 scale.

- Characteristic Detection Models – a set of 22 binary classifiers, each predicting the presence or absence of a specific wound characteristic.

The model outputs can be represented as:

Wound Stage (categorical):

Predicted class:

Wound Intensity (continuous):

where is the model’s clipped continuous prediction representing wound intensity or severity.

Wound Characteristics (binary):

For each characteristic :

Predicted presence:

This system comprises an ensemble of independent models, each trained separately for its respective task (stage classification, intensity regression, and characteristic detection). Although independent, the models use harmonized preprocessing, consistent labeling conventions, and aligned output formats to ensure comparability and ease of clinical interpretation. This design provides a consistent, quantitative, and reproducible framework for wound assessment, compatible with standardized clinical tools such as AWOSI (Automated Wound Objective Severity Index) and established wound staging protocols.

Objectives

Wound Edge Characteristics

Damaged Edges

- Support identification of compromised wound margins, which indicate poor healing potential and increased risk of chronic wounds.

- Enable treatment planning by objectively documenting edge viability and guiding debridement decisions.

Justification: Damaged wound edges are associated with delayed healing and predict chronic wound development (OR 3.2-4.5) [44].

Delimited Edges

- Assess wound boundary definition, which indicates healing progression and epithelialization potential.

- Support prognostic assessment of wound healing trajectory based on edge clarity.

Justification: Well-delimited edges correlate with improved healing outcomes and reduced time to closure [45].

Diffuse Edges

- Identify poorly defined wound boundaries, indicating inflammation, infection, or underlying pathology.

- Flag high-risk wounds requiring enhanced monitoring and intervention.

Justification: Diffuse wound edges are associated with higher infection rates (2.5-fold increase) and impaired healing [46].

Thickened Edges

- Detect hyperkeratotic or rolled edges, which represent mechanical barriers to epithelialization.

- Guide debridement strategy by identifying edge pathology requiring intervention.

Justification: Thickened wound edges require mechanical or surgical debridement to facilitate healing progression [47].

Indistinguishable Edges

- Identify severe edge compromise where wound boundaries cannot be clinically determined.

- Flag critical wounds requiring urgent specialized wound care intervention.

Justification: Indistinguishable edges indicate severe tissue damage and predict poor outcomes without aggressive intervention [48].

Perilesional Characteristics

Perilesional Erythema

- Detect inflammatory response in tissue surrounding the wound, indicating infection risk or inflammatory conditions.

- Monitor treatment response by tracking changes in perilesional inflammation.

Justification: Perilesional erythema >2cm from wound edge is 90% sensitive for wound infection [49].

Perilesional Maceration

- Identify moisture-related damage in periwound skin, which compromises healing and increases wound size.

- Guide moisture management and barrier protection strategies.

Justification: Perilesional maceration increases wound enlargement risk by 60-80% and delays healing [50].

Tissue Characteristics

Biofilm-Compatible Tissue

- Detect visual indicators of biofilm presence, which represents a major barrier to healing.

- Guide antimicrobial strategy by identifying wounds requiring biofilm-targeted interventions.

Justification: Biofilm presence extends healing time by 3-4 fold and increases infection risk [51].

Affected Tissue Types

Encompasses:

-

Bone and/or adjacent tissue

-

Dermis/Epidermis

-

Muscle

-

Subcutaneous tissue

-

Scarred Skin

-

Assess wound depth and tissue involvement, which determines staging, treatment approach, and prognosis.

-

Enable precise wound classification according to depth-based staging systems.

-

Guide surgical planning and reconstructive approach based on tissue layers involved.

Justification: Accurate tissue depth assessment is fundamental to wound staging and treatment selection, with depth being the strongest predictor of healing time [52, 53].

Exudate Characteristics

Fibrinous Exudate

- Identify normal healing exudate, which indicates active wound repair processes.

Justification: Fibrinous exudate represents physiologic healing response [54].

Purulent Exudate

- Detect infection indicators requiring antimicrobial intervention.

Justification: Purulent exudate has 85-95% positive predictive value for wound infection [55].

Bloody Exudate

- Identify vascular injury or fragile granulation tissue.

Justification: Bloody exudate may indicate trauma, friable tissue, or neovascularization [54].

Serous Exudate

- Assess normal wound exudate in early healing phases.

Justification: Serous exudate is characteristic of inflammatory phase healing [54].

Wound Bed Tissue Types

Scarred Tissue

- Identify mature scar formation within wound bed, indicating healing progression.

Justification: Scar tissue formation represents advanced healing stage [56].

Sloughy Tissue

- Detect devitalized tissue requiring debridement for healing progression.

Justification: Slough presence delays healing and increases infection risk by 40-60% [57].

Necrotic Tissue

- Identify non-viable tissue requiring urgent debridement.

Justification: Necrosis presence is absolute indication for debridement and predictor of poor outcomes [58].

Granulation Tissue

- Assess healthy healing tissue formation, indicating active repair.

Justification: Granulation tissue presence is strongest predictor of healing success (OR 8.5) [59].

Epithelial Tissue

- Detect epithelialization, indicating advanced healing and imminent closure.

Justification: Epithelialization is the final healing phase and predictor of imminent wound closure [60].

Image-based Wound Stage Assessment

- Provide standardized diagnostic support according to internationally recognized wound classification systems.

- Enable treatment protocol selection based on validated stage-specific guidelines.

- Facilitate outcome prediction using stage-based prognostic models.

- Support documentation and reimbursement with objective classification.

Justification (Clinical Evidence):

- Wound staging is fundamental to treatment planning, with stage determining intervention intensity and expected healing time [61].

- Inter-observer agreement for manual staging shows moderate reliability (κ = 0.55-0.70), highlighting need for objective tools [62].

- Stage-based treatment protocols improve healing rates by 25-35% compared to non-standardized care [63].

Wound Characteristic Assessment

- Provide composite severity assessment integrating multiple wound characteristics into a single validated score.

- Enable objective severity stratification for clinical decision-making and resource allocation.

- Track healing progression using standardized numerical scale over time.

- Facilitate clinical trial endpoints with validated, reproducible severity metric.

Justification (Clinical Evidence):

- Composite wound scores like AWOSI show strong correlation with healing time (r = 0.72-0.85) and clinical outcomes [64].

- Validated wound intensity scores improve inter-observer reliability from κ 0.45-0.60 to κ 0.75-0.85 [65].

- Longitudinal wound intensity tracking enables early identification of non-healing wounds (sensitivity 78-85%) [66].

Endpoints and Requirements

Performance is evaluated using task-appropriate metrics for each output type: RMAE for ordinal categorical staging, Balanced Accuracy for binary classifications, and RMAE for continuous intensity scoring.

| Output Type | Specific Output | Metric | Threshold | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categorical (0-4) | Wound Stage | RMAE | ≤ 10% | Outputs consistent with expert consensus. |

| Regresion (0-20) | Wound Intensity | RMAE | ≤ 24% | Outputs consistent with expert consensus. |

| Binary | Edge characteristics (5) | BA | ≥ 50% | Outputs consistent with expert consensus. |

| Tissue types (5) | BA | ≥ 50% | Outputs consistent with expert consensus. | |

| Exudate types (4) | BA | ≥ 50% | Outputs consistent with expert consensus. | |

| Wound bed tissue (5) | BA | ≥ 50% | Outputs consistent with expert consensus. | |

| Perif. features and Biofilm-Comp. (3) | BA | ≥ 55% | Outputs consistent with expert consensus. |

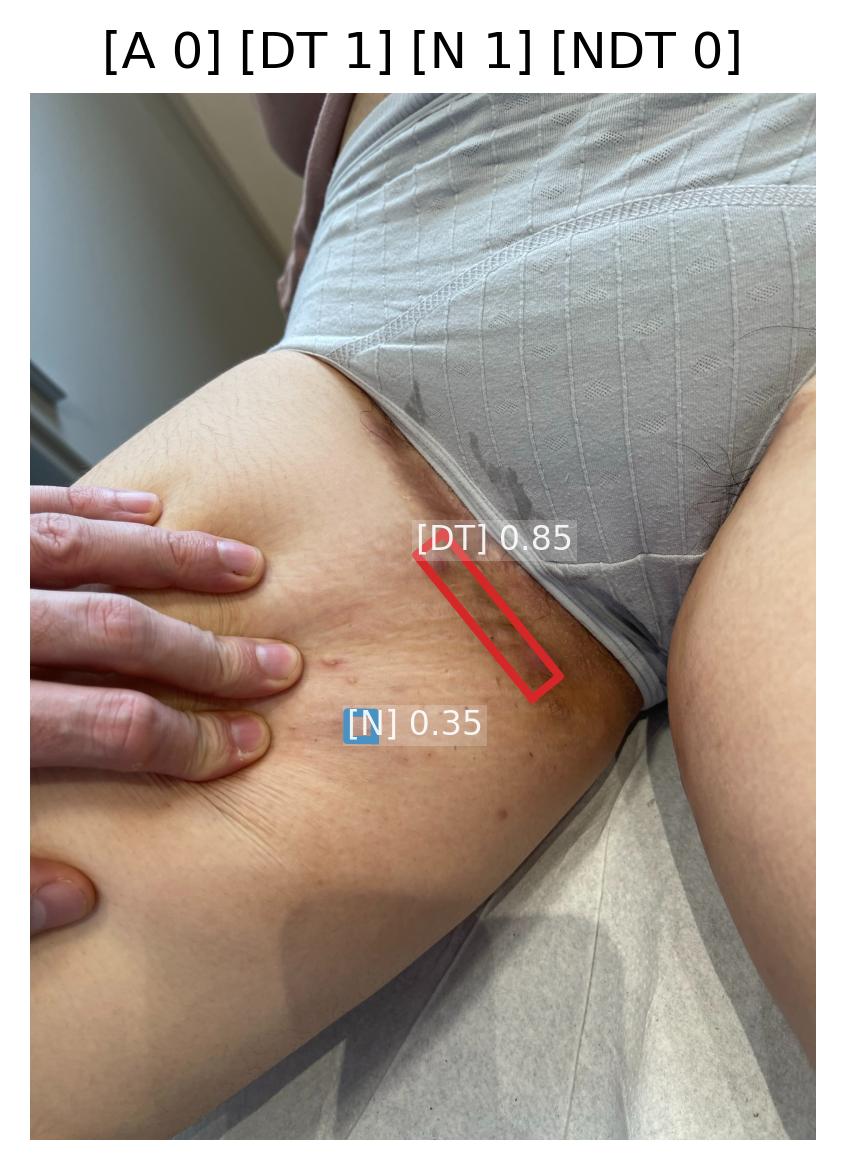

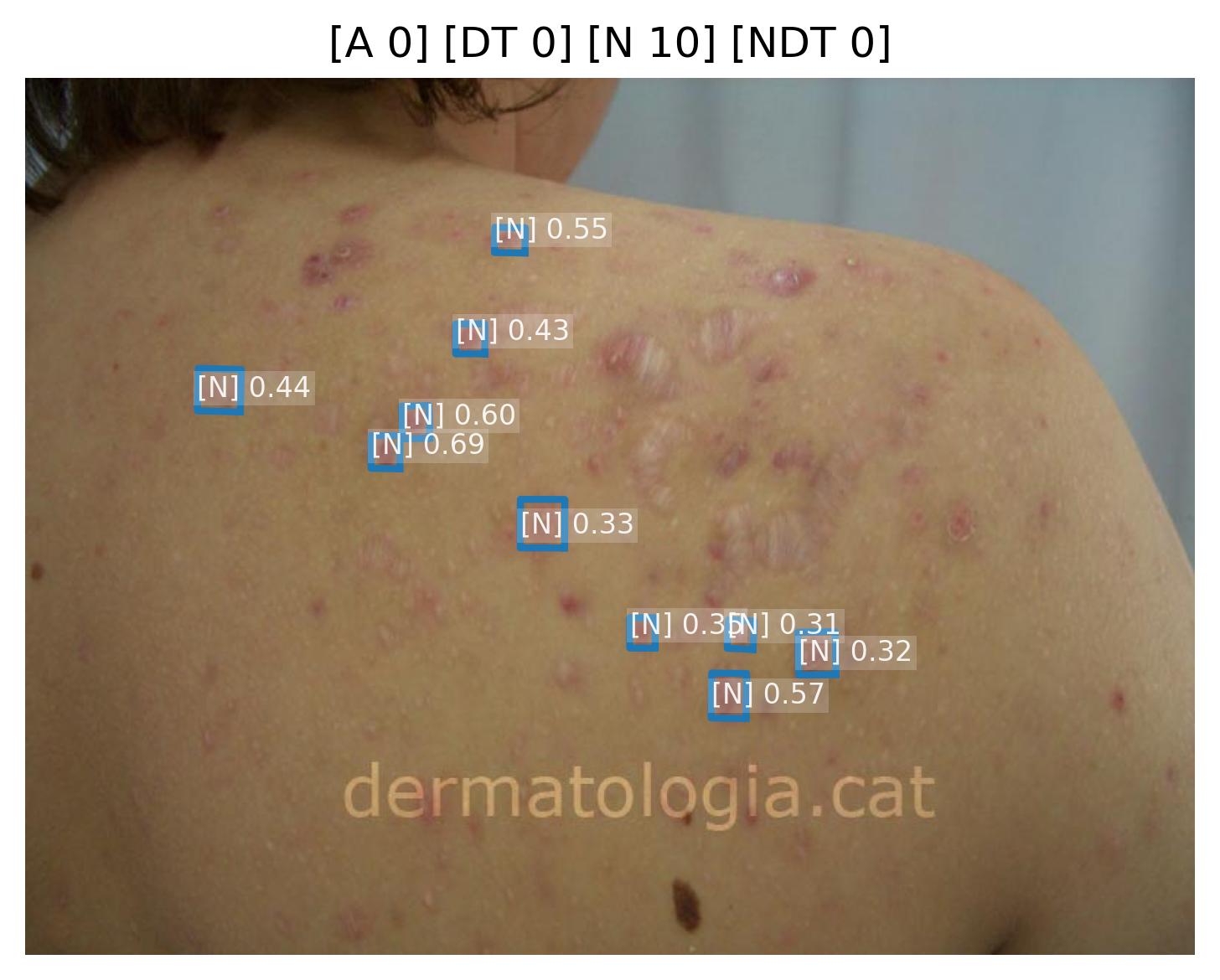

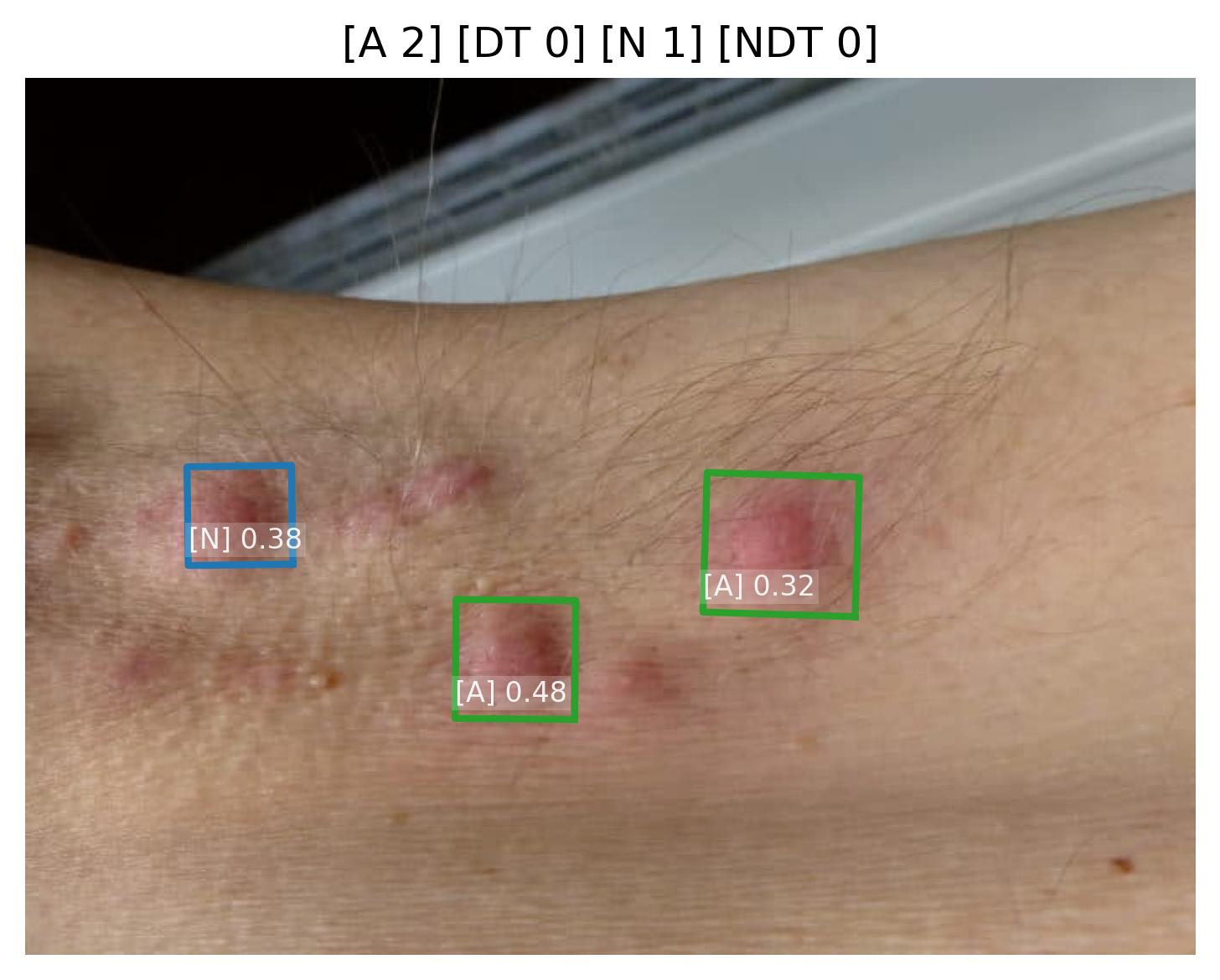

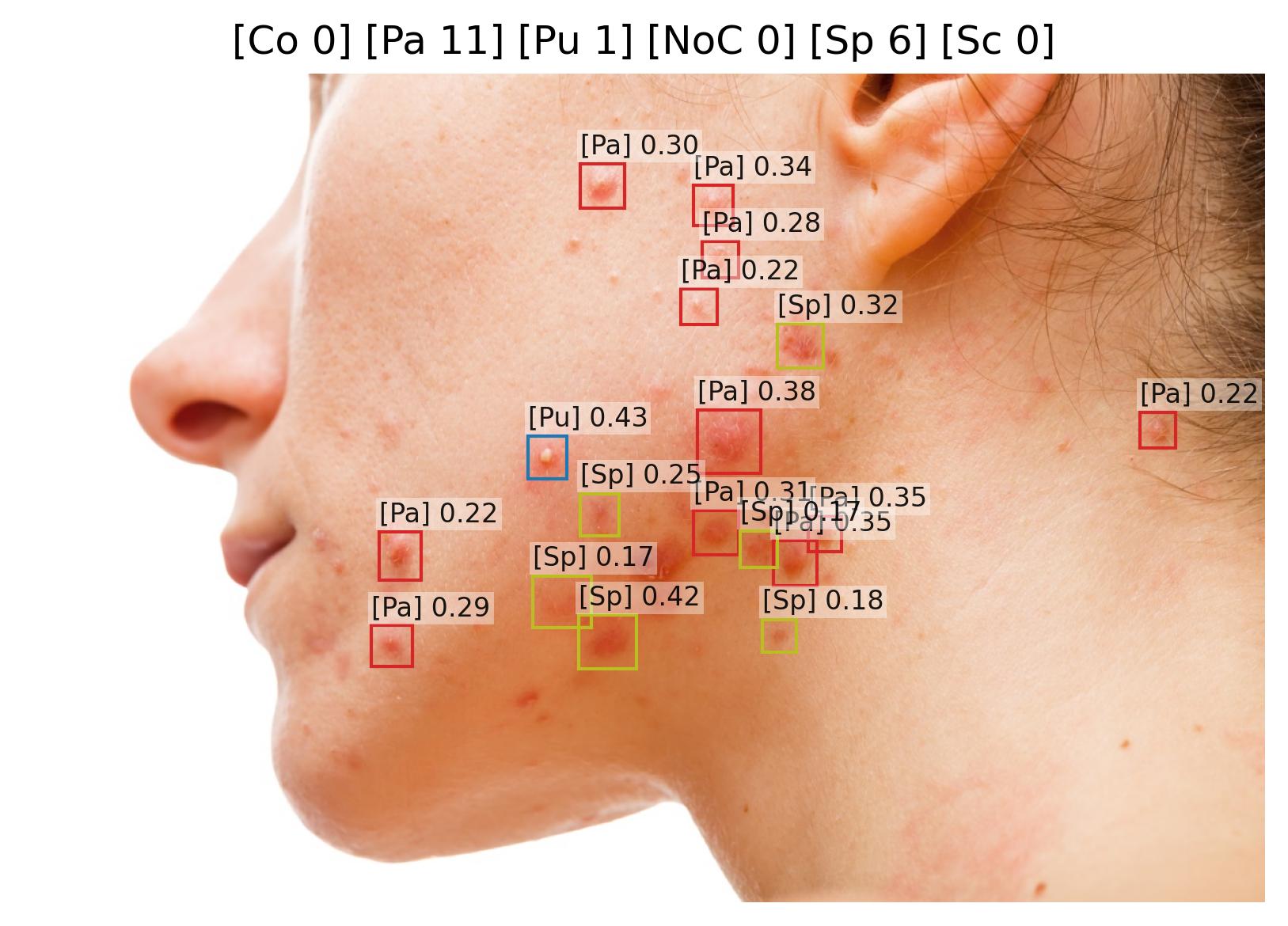

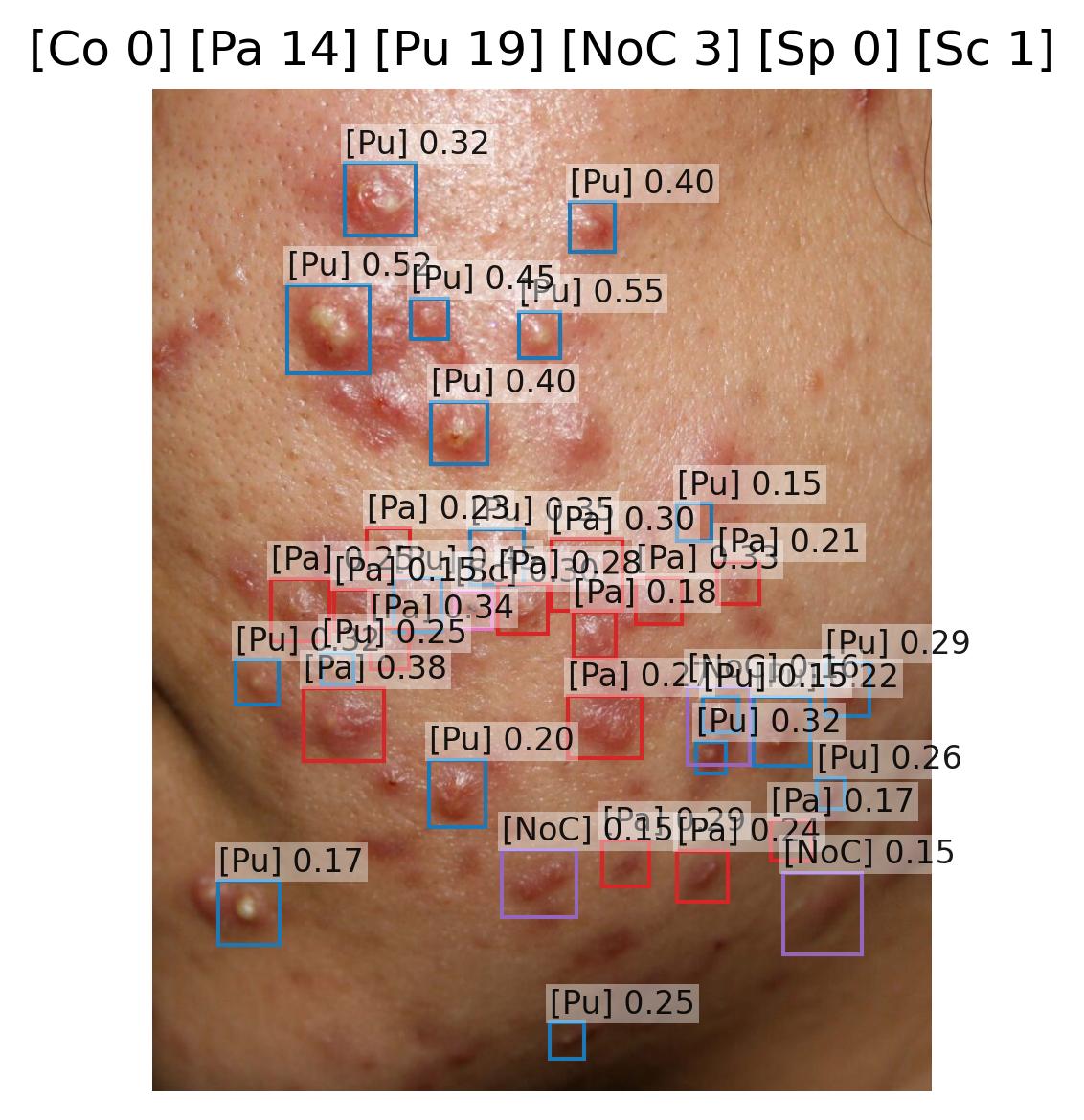

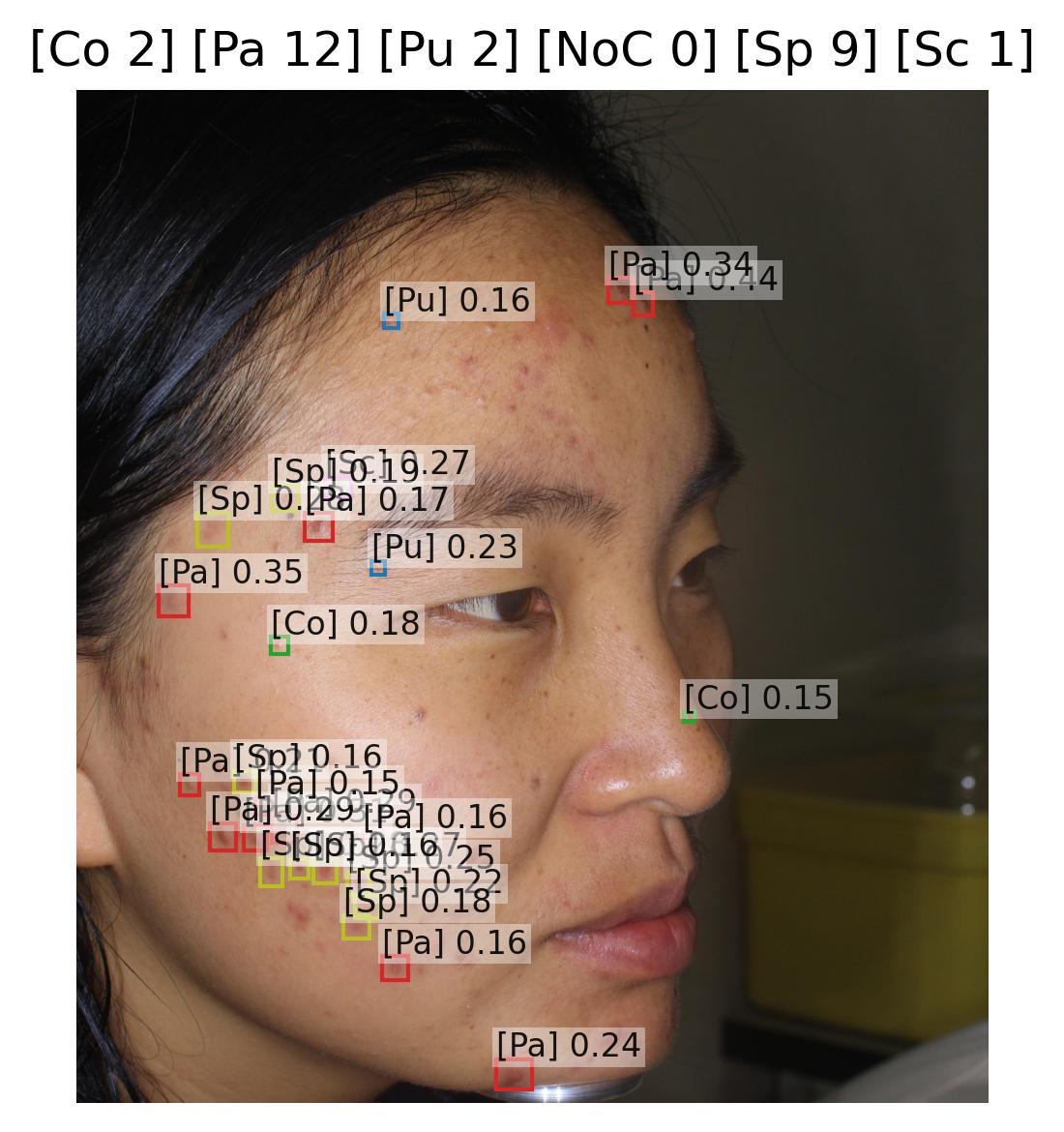

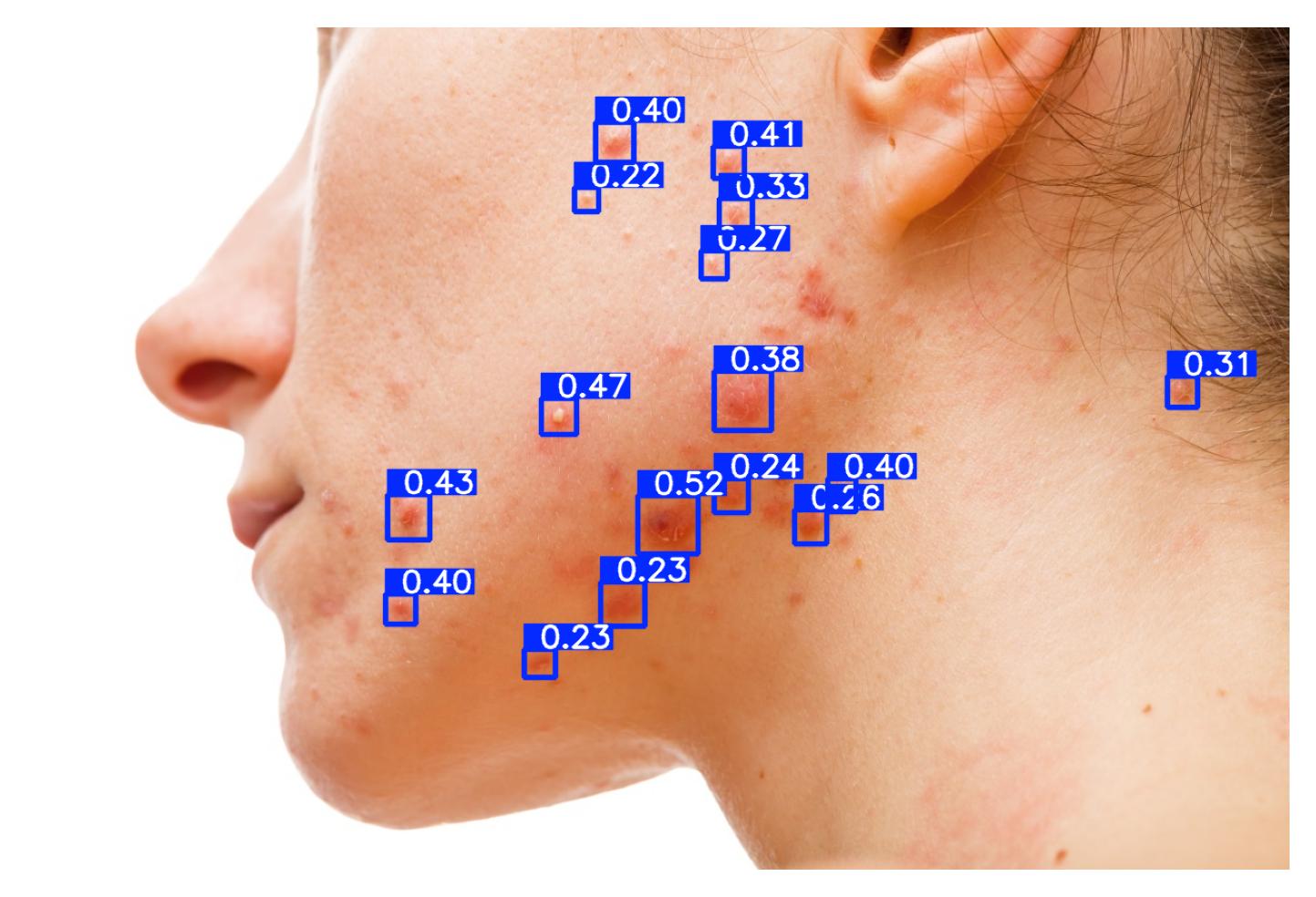

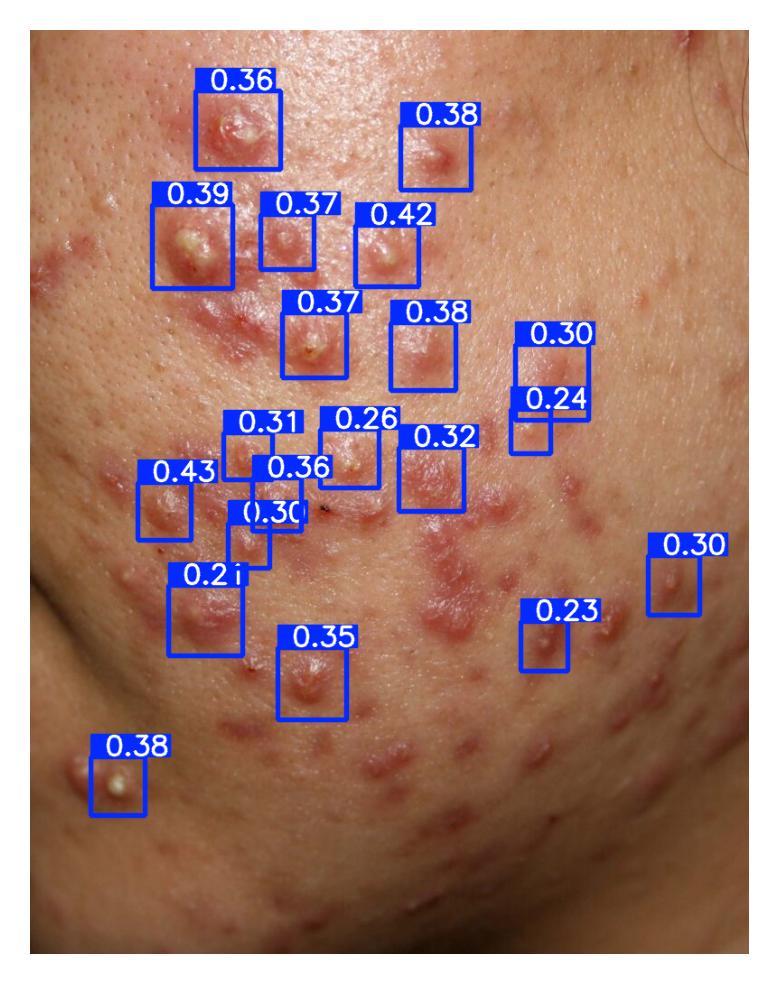

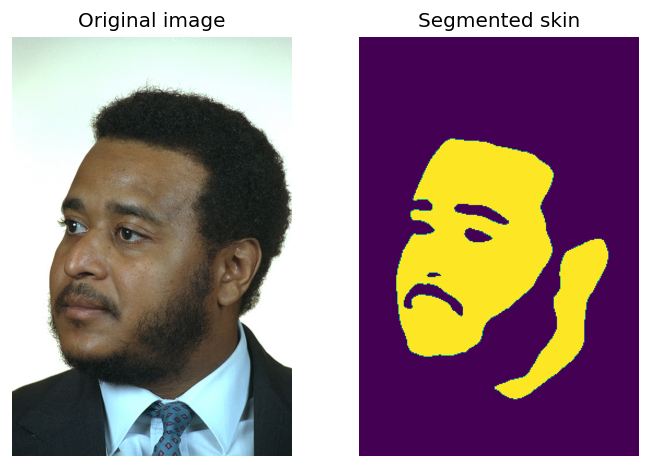

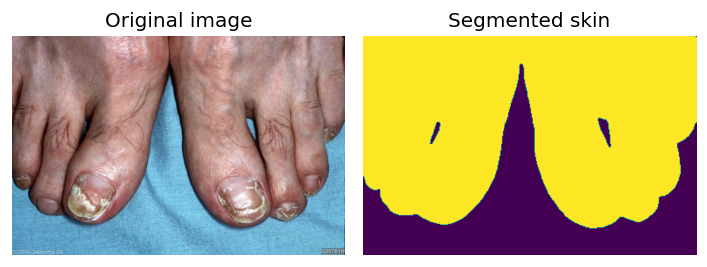

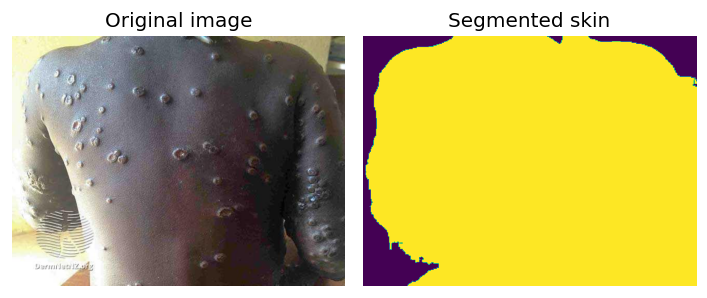

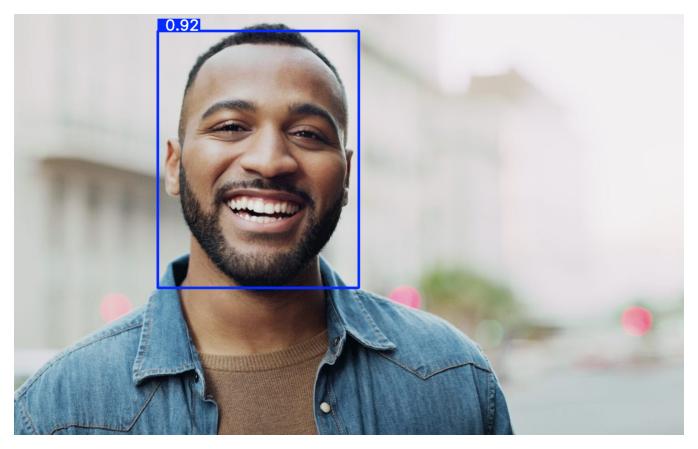

All thresholds must be achieved with 95% confidence intervals.